Schnelles Grünzeug

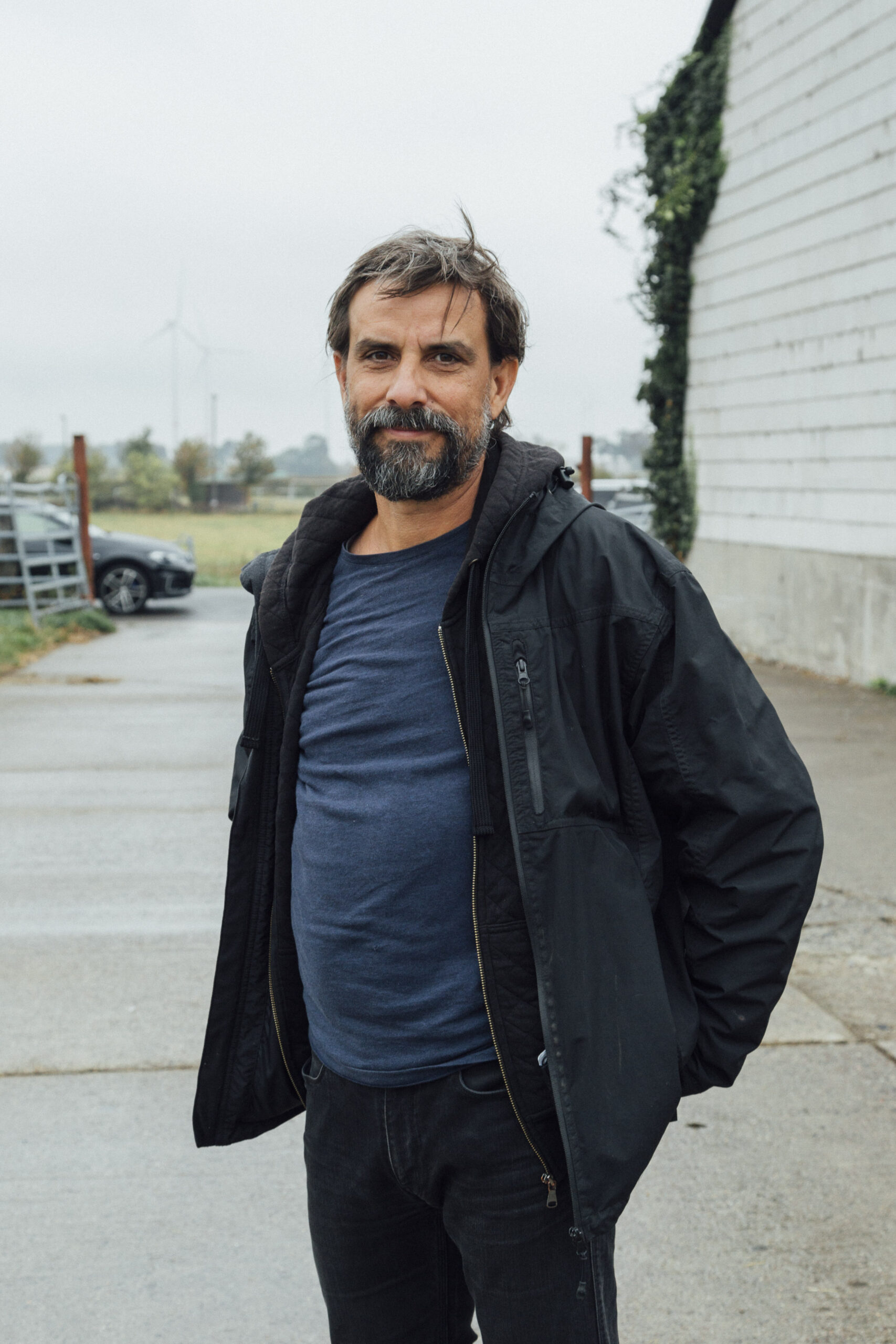

Olaf Schnelle lives and works between the Mecklenburg Lake District and the Baltic Sea in the north-eastern part of Germany where he grows and ferments vegetables in his market garden and manufactory. We talk to him about the importance of diversity and high soil fertility, and how real prices could change the food system.

Olaf, what does your nursery consist in?

I have been running the nursery Schnelles Grünzeug for 20 years, although term nursery is now a bit too narrow, because in addition to the nursery I also run a manufactory in which I ferment both my vegetable surpluses and those of the neighboring nurseries. I use lactic acid fermentation for a wide variety of vegetables, which has reached quite a large scale by now. I now have five employees – thank God, otherwise I wouldn’t be able to do this interview (laughs).

What are the issues that most influence your work?

Increasing diversity is one of the central themes in my work, in every respect. Diversity always has a stabilizing effect, on everything. This is reflected in every area of my life – by making my market diverse, I am less likely to get into economic difficulties, which is even more important, especially in the current times. By developing the soil life as diverse as possible, the soil becomes more fertile. And also, by having contact with people, for example conventional farmers, who do things very differently from me, I get diversity. Even if it is often frustrating, it is still a good, important exchange, because I want to understand why they work the way they do.

What insights do you draw from this exchange?

Through contact, you notice things that you might not have noticed in a direct confrontation. For example, that my neighbor with 2500 hectares of land is taking the same soil culture course that I attended years ago. Or that he is now starting agroforestry and is suddenly applying compost to his land, this means that his approach to green manure is changing.

Is it your goal to influence other farmers through your work?

I am very happy to see that my neighbors have started to think more ecologically. This in turn will be taken seriously and closely observed by their colleagues, so it can have a wider impact. If it starts to change certain things now, it will have an impact on many.

What excites you most about your work and why did you decide to become a gardener?

For a long time, I thought that growing your own vegetables offered a high security value. Moreover, it is simply a very beautiful profession with which one can earn a living. However, the material, financial aspects have also become more important to me as a person who must live in a completely capitalistic environment. From the beginning, I only wanted to do organic farming, but always in a way that would not be a deterrent to others. As an organic farmer, I don’t want to convey the image of being starving, as was the case with some of my colleagues. I find that very unfavorable, especially for young people – but that’s exactly who we need as successors. That’s why a certain economic orientation has been important to me from the beginning. This has brought me a lot of criticism in the eco-scene in which I move.

In the meantime, however, I have noticed how much interest there is in my nursery, which is also due to the fact that I manage to combine ecological and economic aspects. And it is simply a great joy to see how basic convictions in fact come to work – to see how my soil becomes more and more fertile, even though I cultivate it, that thrills me.

That soil management and fertility are mutually exclusive is still a widespread fallacy, isn’t it?

In our studies we were taught that it is an impossibility to grow vegetables without losing fertility. The task was always to counteract the loss by means of tricks like chemical fertilization. In the meantime, I can say that I have a farming system here that works without any additional purchase of fertilizers. This is because our cultivation methods generate the nutrients themselves, the nutrient cycle virtually closes by itself. It’s a complex process; seeing how it works, or how things work that people always said would never work that way, is a lot of fun, and there’s also a certain joy of discovery involved.

How did this develop exactly?

You suspect certain things throughout your life, work amorphously towards a goal – and then suddenly there is an initial ignition in which you can move all the factors that you have already sensed are effective into an orderly system.

In my case it was a soil culture course three years ago in which all the findings came together and made a logical whole. I have Dietmar Näser to thank for that, who teaches a great, practical soil science. On the one hand, it’s based on extremely complex theory, but on the other hand, it’s totally practical – that’s the beauty of it.

What does the collaboration with your customers look like, do you discuss together what the requirements are for the products?

I have often tried to get into a kind of cultivation planning with my clients, but I realice how difficult it is – this is mainly because cooks are not used to thinking ahead in such long cycles, because who knows today what they will cook in 10 months? Knowing this would be extremely valuable for us gardeners, as we now must buy our seeds for the coming year in November, December. I have come to realice, and I mean this in a non-judgmental way, that very few cooks can think like that and I suspect it would massively disrupt the creative cooking process. You need flexibility to be creative. Often, what’s available on the day simply determines what ends up on the table – in case of doubt, this is even more appealing to me than having everything meticulously planned down to the smallest detail.

What responsibility do farmers and gardeners have towards their environment today?

A very massive one. In Germany, we use a gigantic amount of land for agriculture. All farmers who claim that they can do whatever they want with their land are simply acting ignorantly towards society. Because our actions influence biodiversity, soil quality, emissions. We have an enormous influence on climate change, but unfortunately we gardeners and farmers rarely realice how big this influence really is. If farmers would realice that they are currently seen as polluters, but at the same time have the chance to be exactly the opposite, they could present themselves as a huge valuable part of society. But constantly ignoring themselves for producing all the food is just a shield that distracts from the real responsibility.

That is one thing, the other is quite simple: we farmers and gardeners have a responsibility to produce and provide our society with genuinely healthy food. This is quite banal, but unfortunately not everything that grows in the fields is full-fledged. Only full-fledged plants are also full-fledged food.

Why did you become a member of the community?

I’m very interested in the exchange, both with colleagues and customers. I’m far away from any scene here, three hours away from the culinary hotspots, but I want to earn my living by reaching exactly these people. When you are so far away, you must remain attractive in your developments and keep up with the times, observe everything. For that, the constant exchange within a group is enormously important.

The other thing is that there are really a lot of nice people with whom it’s just really fun to work together. They are not only nice in some way, but also really make a difference. And because the community is placing more and more emphasis on imparting knowledge and building up the next generation of professionals, I feel I’m in really good hands there, because that’s my current life topic. So, there is a nice convergence of interests.

“Showing them a way to act as equal market participants and get away from their comfortable subsidy thinking would change the whole game. Which is also very political as well.”

What are the goals within the community that you want to achieve?

I’m 55 now and I’ve created something here – I think now it’s time to pass on my know-how, because otherwise it will be lost at some point. That’s why I’m currently working on setting up an exchange platform that aims to promote the next generation of my profession, that is to show how to garden, how to ferment, but also to strengthen the overall exchange within the different trades. In my professional life, I have been confronted with so much ignorance, and we absolutely must change that. Sometimes cooks don’t know anything about the work of a gardener and, conversely, we gardeners don’t learn anything about what is interesting for cooks. I am often amazed at what they essentially pay attention to. You present interesting plants, but your counterpart looks at the herb next to it.

I also want us to be able to create a basis for running our work economically in a sustainable way. This means that we must grow as a community – not by hook or by crook, but through qualitative growth accompanied by economic strengthening.

If we zoom out again from the smaller cosmos of the community and go into the big picture – have you noticed any noticeable changes in the food system in recent years?

With statements like that, you run the risk of thinking too much within your own bubble, of naming issues that perhaps for the whole society don’t exist at all. But I do think that people are now thinking more about food and the way land is cultivated. There are many small and larger active movements that pursue very similar goals as we do as a community. And of course, they have an influence on the whole food system, even if it is still rather marginal. But when I see that even Lidl now has permaculture products from Spain in its assortment, one can either condemn it or regard it as progress, because this permaculture farm is massively different from the other farms there. You just must walk through the plantations – the farm Lidl works with, for example, shows no soil erosion. The fact that Lidl is moving in this direction has of course something to do with all of us, otherwise they wouldn’t be doing it. So, yes, I see a change that I hope will continue to spread. But we will have to remain very active for a long time.

Moreover, we are now experiencing an industrialization within the organic scene, which cannot be the point. Even though every industrially produced product is still a little bit more valuable for the environment than every conventionally produced product.

Which topics within food production do you see the greatest need for change and action?

The most important thing, because it is so obvious, is that we need to get to total cost accounting. That makes more sense than any food traffic light. If CO2 release and storage are reflected in the price, no one can say anymore that people want cheap, let’s say milk. When my neighbor with 1500 cows in his barn wonders why I prefer to buy expensive oat milk instead of cheap cow’s milk, I can only reply that he should calculate what his farm really costs, what it costs the environment to be polluted by all the manure and exhaust fumes. If you could hang prices on it, your milk would no longer be available for one euro for the final customers, but they would have to pay much more money, which could then be used to compensate for the damage caused. That would be a really important factor: to give food real prices that consider both the environmental impact and the normal needs of the producers.

So the politically determined standard must be applied quite differently?

Exactly. Just as it would be a political decision to no longer label organic food as organic, but simply as food and the conventional products would have to be labelled with a warning label. That would be the more realistic economy.

This would have to be broken down into very concrete, easy-to-implement measures. At the moment, for me, the most important lever is the soil. We gardeners all work with this limited medium, but the importance of the soil is clear to very few people, both on the consumer side and, frighteningly, on the producer side. Yet the soil can be precisely the lever through which organic farmers can enter into conversation with conventional producers. It is important for farmers to be able to talk to each other at all, without making this distinction between organic and non-organic. It is important that we encourage the farmers and show them how they can move from being pure suppliers back to being sellers. They produce something over which they have no power to determine the price, because they always must accept the price they are given. The conventional farmers unfortunately suffer from a serious inferiority complex because they drive big tractors but are not able to sell their wheat. It’s really humiliating, you have to imagine. Showing them a way to act as equal market participants and get away from their comfortable subsidy thinking would change the whole game. Which is also very political as well.